🧠 The United States turned a 15 year old Afghan boy into a contract killer, unleashed him on his own people for a generation, then brought him to America and abandoned him. Guess how it turned out?

If you turn teenagers into contract killers and give them nothing but paperwork and poverty when you’re done, this is what you get.

Family,

Before we get into this, I need to ask those of you who can to click here to become a member of The North Star. We keep this work free for the world — for readers in war zones, for veterans, for immigrants, for people living in deep poverty, and for young people trying to understand what this country really is. That only happens because a smaller circle of you carries the cost. Your membership keeps this reporting free for them, and even for you when you can’t afford to pay. If you’re able to hold this up at a higher level, please click here to join as a monthly, annual, or founding member.

This Was Not a “Senseless” Tragedy

Last week, just two blocks from the White House, 20-year-old National Guard member Sarah Beckstrom was shot and killed. Another Guardsman was gravely wounded. It didn’t happen in some neglected corner of America. It happened in one of the most heavily surveilled, heavily policed, heavily funded security zones on Earth.

Sarah was part of something called the “DC Safe and Beautiful Task Force.” That is the official name. The mission, as advertised, is to fight crime and “beautify” the city. The military even made a glossy promotional video of soldiers in uniform picking up trash around Washington, D.C. That is what Sarah was doing in the nation’s capital — serving as a kind of uniformed stage prop in a political theater of “safety” — when she was shot.

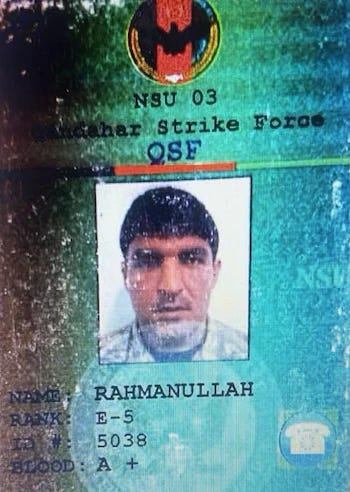

The alleged shooter is 29-year-old Rahmanullah Lakanwal, an Afghan man who had been granted asylum in the United States after serving in a CIA-backed paramilitary unit in Afghanistan.

If you stick with the official talking points, the story stops right there: a dangerous foreigner, an ungrateful refugee, proof that we were too generous and too soft. But if you pull the camera back and actually look at who this man was, what we did to him, and how we left him, a different picture comes into focus. This man was basically Jason Bourne.

This shooting was not a strange bolt from the blue. It was a straight line.

Turning a Teenage Villager Into a War Asset

Reporting from the New York Times traces Rahmanullah’s life from a tiny wheat-farming village near Khost to a CIA-run paramilitary unit in Kandahar and, eventually, to an apartment in Bellingham, Washington.

He was a small child when the U.S. invaded Afghanistan after 9/11. By his mid-teens — sources say as young as fifteen — he was in the 03 Unit, one of the so-called “Zero Units” funded, trained, and directed by the C.I.A. These were not ordinary Afghan soldiers. They were informal death squads tasked with kicking down doors in the middle of the night, hunting suspected Taliban, and doing the dirty work the U.S. did not want to put its own face on. Human Rights Watch has accused the Zero Units of extrajudicial killings, disappearances, and attacks on medical clinics.

In other words, the United States took a village kid and turned him into exactly what it needed: a contract killer pointed at its enemies, operating in a gray zone where the laws of war were more suggestion than requirement.

Friends from his village told the Times that when he came home on breaks, he was not the same person. The outgoing teenager who liked picnics and socializing became withdrawn and tense. He did not want to go out. He did not want to talk about his work. He asked people not to ask. He reportedly told others that the bodies and blood he’d seen had shaken him.

If an American teenager came back from multiple tours in a special operations unit talking like that, we’d at least use the words “PTSD,” “moral injury,” “combat trauma.” Whether we’d give him true care is another matter — but we would understand that something profound had been done to his mind.

With this Afghan teenager, we took his biometrics, logged his missions, and kept sending him back out.

From Kabul Airport to a Dark Room in Washington State

When Kabul collapsed in 2021, these Zero Units were still being run hard. American commanders asked them to help secure the perimeter of the airport during the frantic evacuation. In return, U.S. officials promised to get them out — a “moral obligation,” they called it, to protect the men who had killed and risked death on our behalf.

So Rahmanullah and his family were airlifted out as part of Operation Allies Welcome. Like about 190,000 other Afghans, they arrived in the United States on temporary parole and were told to apply for permanent status.

After the usual blur of military bases and processing centers, they landed in Bellingham, Washington, a liberal town of about 97,000 near the Canadian border. A Christian resettlement group, World Relief, took on their case. Volunteers helped with housing, paperwork, school enrollment, job applications.

At first, they built what looked like the start of a new life. They decorated their home with Afghan rugs and floor pillows. His wife sewed cushions with a donated machine. They drank tea on the carpet with other Afghans and American visitors. He took his five sons to the local mosque. It looked, for a moment, like that official moral obligation might mean something.

Then the war inside him caught up.

By early 2023, a volunteer who worked closely with the family watched him unravel. He quit his job. He withdrew into a darkened bedroom and often refused to come out. He stopped attending English classes. He avoided visitors. He stopped paying rent, putting the family at risk of eviction. When his wife left the house, he sometimes did not even dress or bathe the boys.

He also began getting into his car and driving for days at a time, alone, without explanation — to Chicago, Phoenix, Indianapolis — posting pictures from the road as his family’s life disintegrated behind him.

In January 2024, this volunteer put her fear into writing. In an email later obtained by reporters, she wrote: “Rahmanullah has not been functional as a person, father and provider since March of last year.” She said she believed he was suffering from post-traumatic stress from his work with U.S. forces and that he might also be manic depressive. She described his latest cross-country drive as a “manic trip.”

She tried to sound the alarm. The email went to a friend involved in refugee work, who passed it along to a national organization. A program officer eventually visited Bellingham to meet with Afghan families generally, but said he didn’t remember hearing about this specific case and never met him.

Meanwhile, the immigration system kept doing what it does. His temporary parole was renewed. He filed an asylum application. Because of a legal settlement, his case was expedited. In April of this year, his asylum was granted. The Biden administration and the Trump administration both effectively signed off on his presence in this country.

On paper, everything looked fine. In reality, the United States had taken a man it had turned into a weapon, transplanted him into a small American city with some donated furniture and well-meaning volunteers, given him no serious mental health care, and quietly walked away.

Anyone who has paid attention to what happens to many U.S. veterans will recognize that pattern.

A Country That Breaks Its Killers and Then Acts Surprised

We have seen this movie before.

We send very young people — often from poor families and impoverished towns — into wars built on lies. We train them to kill. We expose them to horror. We often involve them in things that eat at their conscience long after the last shot is fired. Then we bring them home, throw them back into everyday life with a pamphlet and a number to call, and tell them to be grateful.

When they start to fall apart, we see domestic violence, bar fights, quiet addictions, suicide attempts, flashbacks, homelessness. Sometimes we see worse: mass shootings, family annihilations, workplace attacks. You don’t have to dig far into the history of American mass shootings to find a familiar path: veteran, untreated trauma, red flags, no real intervention, then carnage.

We do this to our own kids in uniform. So of course we did it to the Afghan teenagers and twenty-somethings we turned into instruments of our policy.

That is what makes this case feel so grimly predictable. This is not random chaos. It’s the logical product of a system that is brilliant at inventing ways to kill and astonishingly bad at tending to the human beings it turns into killers.

The Security State That Misses What Matters

My brother Ken Klippenstein wrote about this in his piece, “The Government Killed National Guard Member Sarah Beckstrom.” He laid out what should be an obvious question: if this is precisely the kind of threat our multi-trillion-dollar security state claims it is built to detect and prevent, what exactly are we paying for?

Since 9/11, we have thrown dizzying amounts of money at federal agencies tasked, on paper, with keeping us safe: the FBI, DHS, the CIA, the NSA, Joint Terrorism Task Forces, fusion centers, “insider threat” programs, behavioral analysis units, a tightening web of watchlists and background checks. In Washington, D.C. alone, there’s a small army of federal and quasi-federal police forces operating within a few miles of each other.

This is on top of the vetting systems that were supposed to flag someone like this long before anything happened: refugee and asylum screening, gun purchase background checks, intelligence databases, and all the rest.

Yet here, in this case, you had a man whose entire adolescence and early adulthood were consumed by secret warfare, whose friends and community knew he was deeply traumatized, whose volunteer caseworker wrote in plain language that he had ceased to be functional, and who was clearly spiraling.

The system was not starved of information. It was indifferent to what that information meant.

And after the shooting, the reflexive response from the same politicians and agencies has been the same old set of moves: more National Guard deployments, more money for the Department of Homeland Security, more calls to crack down on refugees. Mission creep continues. Accountability does not.

Responsibility and Predictability

None of this analysis is meant to minimize what happened on that sidewalk.

A young woman is dead. Another soldier is badly hurt. Their families are devastated. The alleged shooter made a horrific choice and should be held responsible for it.

But if we want to keep other people from dying like this, we cannot stop at individual blame. We have to look at the architecture that made this outcome so likely. We have to be honest about what it means to take a fifteen-year-old village boy, turn him into a contract killer in your secret war, move him across the world, and then act like you bear no responsibility for what happens when his mind and life fall apart.

We can hold two truths at once: that the trigger puller bears responsibility, and that the government that trained him, used him, imported him, approved him, and then abandoned him in a dark room bears responsibility too.

If we refuse to see that second part, then we are just waiting for the next version of this story. Different names. Different uniforms. Same arc.

Family, if you value this kind of deep, uncomfortable honesty — if you want someone to connect these dots without bowing to the same institutions that caused the harm — I’m asking you to help me keep doing it. Please click here to become a member so we can keep this work free for the world, especially for people whose stories will never get a press conference or a PR budget. And if you’re able to help hold this up at a higher level, please click here to join as a monthly, annual, or founding member.

Love and appreciate each of you.

Your friend and brother,

Shaun

Don’t Stop Here

If this story is sitting heavy on your heart, don’t just move on to the next headline.

Go read Ken Klippenstein’s piece “The Government Killed National Guard Member Sarah Beckstrom” and really sit with the way our security agencies keep failing at the one job they brag about. Go find the New York Times’ reporting on Rahmanullah’s life — the Zero Unit raids, the fearful silence when he came home to his village, the dark bedroom in Bellingham, the emails that said “he has not been functional” years before a shot was fired in D.C. And then look again at what this country does, over and over, to the people it trains to kill — whether they were born in West Virginia or Afghanistan.

Talk about it with your family, your friends, your faith community, your group chats. Because until we are willing to say out loud that this kind of violence is predictable, baked into the choices our leaders keep making, we will keep pretending that the next version of this story came out of nowhere.

I had to be brutally honest in this piece. American made him into a serial killer, then brought him here and abandoned him. And he kept killing.

As someone who deployed to Afghanistan with the Illinois Army National Guard in 2007, I trained Afghan Border Patrol agents. This story is very believable and, like the article says, we see it over and over in our own military among those who have been traumatized by war. I know many people with PTSD, and have had to come to terms with my own sense of rage at how poorly we did in that theater. As long as we as a country remain committed to profit over people, we will see the fallout in terms of human lives wasted at the altar of corporate greed. We need to not merely protest - we need to build something better. We need to build relationships and communities where people are valued more than whatever money society says they are worth. Our country will not change until our values do. That's the real moral of this story.